Wood rots are caused by several different fungal organisms. They are primarily wound colonizers and can grow in and on both living and dead trees under moist conditions. Virtually any type of wound that exposes the inner wood tissue, such as pruning cuts, ice or wind damage, mowing or weed whacker damage, construction damage, insect wounds, damaged roots, and more, will predispose the tree to attack by any of the wood-rotting fungi. Wood rots spread from these initial infection sites to the heartwood or sapwood of the tree causing discoloration, disintegration, and eventual decay and death of the tree. This process of decay may take anywhere from 3 to 5 years to more than 100 years. Wood rots are classified depending on the part of the tree attacked, i.e. root and butt rots or stem rots. There also are white rots and brown rots, and soft rots. The white rots will most often attack hardwoods (deciduous trees) and utilize lignin as a food source and leave behind the cellulose. Affected wood is soft and spongy in texture. The brown rots will attack mostly softwoods (conifers) and digest cellulose leaving behind the lignin of the cell walls, resulting in a dry rot that crumbles under pressure.

Oftentimes the only indication of a wood rot occurs when major limbs and entire trees are blown-down during heavy wind and rain storms. Symptoms of trees colonized by wood rots include a gradual decline in vigor, sparse foliage, dieback of twigs and branches which are structurally weak and eventual death of the tree. Wood rots predispose the trees to secondary colonization by other microorganisms and insects. It is very important to note that the fungal fruiting structures (conks or mushrooms), which are seen at the trunk base or wound site, can not be used as predictors to estimate when the tree will die. Although the mushrooms usually do not appear until the decay is well advanced, it does not indicate the tree will die immediately. Most wood rots form conks annually. However, these can become inconspicuous as they darken and harden with age resembling the surface roots of the tree (see the Inonotus image below). Trees can live many, many years with wood rot fungi, depending on the extent of colonization by the fungus, the size of the tree, the response of the host tree to the wound (quick healing), the presence of antagonists to the fungus involved, and additional factors related to the general health of the tree (location, proper installation and care, etc).

Management for wood rots in infected trees is extremely limited. The tree will eventually die from the fungal infection but there is no definite time period for when this will occur; it could be months, but more often it is many, many years. Conks or mushrooms of the fungal pathogens will reappear from year to year around the same time. Management, therefore, should be aimed at the following cultural practices to prevent infection from occurring:

- Select and grow trees suitable for a particular site and/or area. Plant vigorous, disease-free stock; plant at the proper depth and in well-drained soil.

- Mulch around trees to limit grass growth directly beside trees and therefore, potential hazards and/or injuries that could result from mowing or edging the lawn.

- Provide adequate irrigation and fertilization to keep the trees in good health.

- Prune young trees to promote good structure and to prevent the need to remove large limbs from older trees (which leaves large wounds for subsequent infections).

- Remove all dead, dying, or diseased branches during the dormant season by making proper pruning cuts (prune outside the branch bark ridge, leaving the ‘collar’ that surrounds the base of each branch to aid in wound healing).

- In general, AVOID wounding the trees at all costs. This will prevent the entrance and colonization by the wood-rotting fungi.

The following are images of common wood rots seen throughout Georgia.

- Inonotus dryadeus (weeping conk fungus) – causes a white rot of roots on living oak tress & rot of dead trees and logs

- Close-up of fresh Inonotus dryadeus conk on pin oak roots.

- Inconspicuous older conk of Inonotus dryadeus

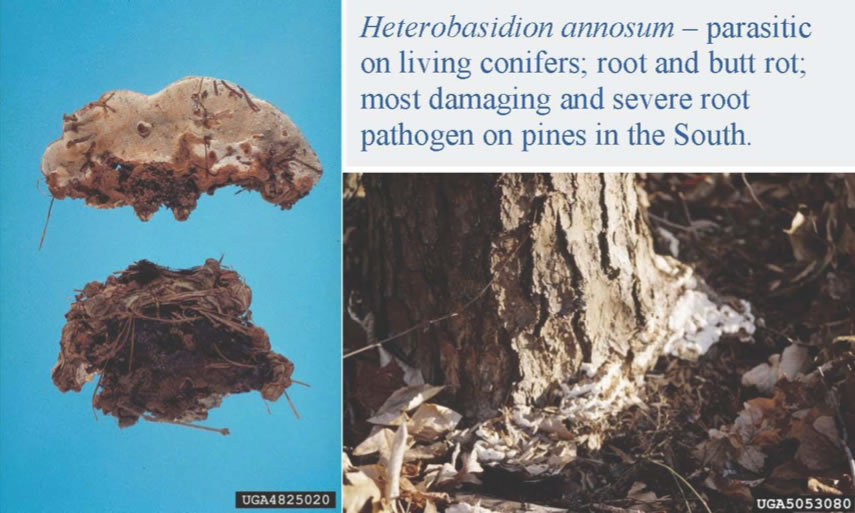

- Heterobasidion annosum – parasitic on living conifers; root and butt rot; most damaging and severe root pathogen on pines in the South.

- Ganoderma lucidum (artist’s conk) – causes a root and basal rot in conifers and hardwoods

- Ganoderma lucidum (artist’s conk) – causes a root and basal rot in conifers and hardwoods

- Grifola frondosa (Hen of the Woods) – white butt rot in conifers and hardwoods

- Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) – parasitic on hardwoods (esp. Oak)

Reference: Homeowner Plant Disease Clinic Report, Nov. 2006, Holly Thornton